|

|

- Search

| Public Health Aff > Volume 4(1); 2020 > Article |

|

Abstract

Objective

Since December 2019, we have been experiencing a COVID-19 pandemic, and local community infections in Korea are on the rise. In particular, places where large numbers of people gather are prone to COVID-19 infections; therefore, how we confront COVID-19 is importantin those places such as hospitals, schools, and gyms. Thisstudy aimed to share lessons from the experience of COVID-19 in the paediatric ward of Asan Medical Centre.

Methods

We used epidemiologic data and contract tracing data to investigate the coping process in Asan Medical Center.

Results

A paediatric patient with confirmed COVID-19 was hospitalized, and the patient and her guardians were placed under cohort quarantine. Subsequently, another guardian in the hospital diagnosed with COVID-19, and asthe quarantine lengthened, people complained. Those under quarantine were released without additional spread.

The first case of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) was reported in December 2019, and we have since entered a pandemic phase [1, 2]. Community spread is occurring widely, due to the rapid transmission of COVID-19 infections. Public places in particular, such as gyms, churches, and hospitals, are prone to viral transmissions [3]. Hospitals especially, are an important site in which to minimize transmission, due to the presence of patients with compromised immune systems. Additionally, when someone who is diagnosed with COVID-19 is in a public place, how this is confronted is important, especially for vulnerable groups such as children. In this manuscript, we describe the process of dealing with COVID-19 patients related to hospital, community, and government responses, in the paediatric ward of the biggest hospital in Korea [4,5].

The epidemiologic data and contract tracing data were obtained to investigate the process of dealing with COVID-19 cases in Asan Medical Center.

The tertiary education hospital in Seoul, Korea confirmed their first paediatric case of COVID-19, prior to which, 132 paediatric patients in Korea were hospitalized for COVID-19. Almost are paediatric patients had been infected by their parents through close contact at home. However, on 30th March, 2020, a nine-year-old female at the biggest hospital in Korea tested positive for COVID-19, after her initial results came back negative. The patient had been receiving treatment in the No.136 ward of the hospital for other conditions since 26th March, 2020. She was tested repeatedly, as she had previously been treated at another hospital in the Gyeonggi province, which subsequently experienced a new cluster of infections.

After five days, a 40-year-old mother of a neonate patient tested positive for COVID-19, and became the hospital’s second case. Her infant was in the same ward as the first patient, and the mother visited that room twice. Health officials brought the mother back to the hospital on the outskirts of Seoul after her COVID-19 diagnosis; however, her infant and husband tested negative for the virus.

The same day that the first patient was diagnosed, the COVID-19 immediate response task force team was organized, consisting of hospital infection control, Korea Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC), Seoul Metropolitan Government, community healthcare centre field management, and provincial epidemiological investigation officers. The task force handled the diagnosis and prevention of hospital infections as follows.

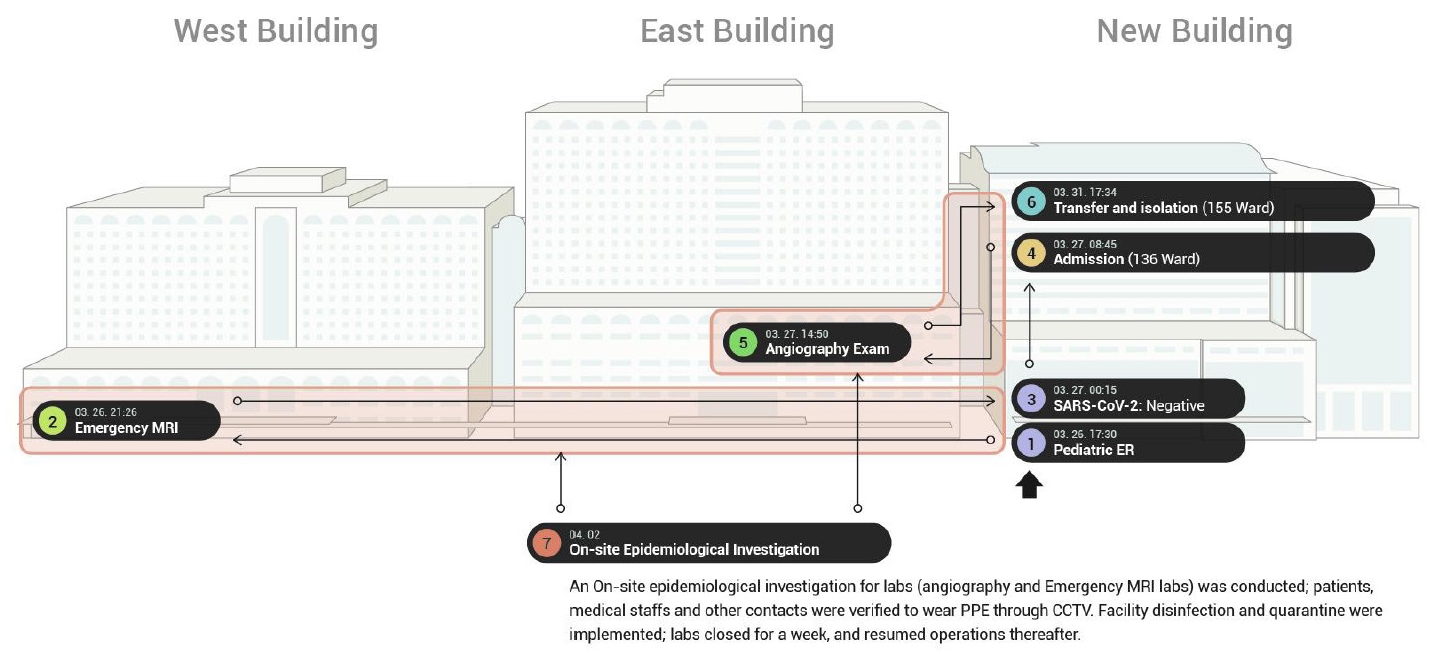

First, the COVID-19 infected child was transferred to a negative pressure isolation room. Then, the other paediatric patients in the No.135 and adjacent No.136 wards were placed under cohort quarantine. The route the patient took through the hospital, including the paediatric emergency room, paediatric emergency x-ray room, magnetic resonance (MR) room, and angiography room, were shut down and disinfected (Figure 1).

Second, an epidemiological investigation was conducted to search for contacts the patient made during her hospitalization. This investigation included a survey, a chart review, and closed-circuit television monitoring. The criteria used for determining what constituted a contact were those defined by the KCDC.

Third, we categorized hospital employees, patients, and their caregivers into three groups according to their risk, based on the epidemiological investigations. The first group (A) was defined as a high-risk contact with direct proven exposure to COVID-19 patients. These individuals each underwent the COVID-19 PCR test and were quarantined for two weeks. The second group (B) was not a high risk, but was an intermediate-risk group that stayed on the same floor as the patient but not in the same room. These individuals each underwent the COVID-19 PCR test all and were quarantined temporarily. The third group (C) was a low-risk group. They were offered the COVID-19 test, and their symptoms were actively monitored.

Throughout this process, a few unintended problems arose. First, in the event of a confirmed case of COVID-19, patient isolation is the basic rule. However, it was impossible to separate the patient from her parents because of her age. To maintain a strict quarantine, not only was medical treatment necessary, but emotional support and staying with parents or caregivers were also necessary. In allowing parents or caregivers to remain with the patient, the infection risk is increased, but the rights of the child are respected. In regards to other quarantined children, the COVID-19 task force permitted parents or guardians to stay in the room with personal protective equipment such as masks, facial shields, gloves, and gowns. They made repeated COVID-19 testing mandatory.

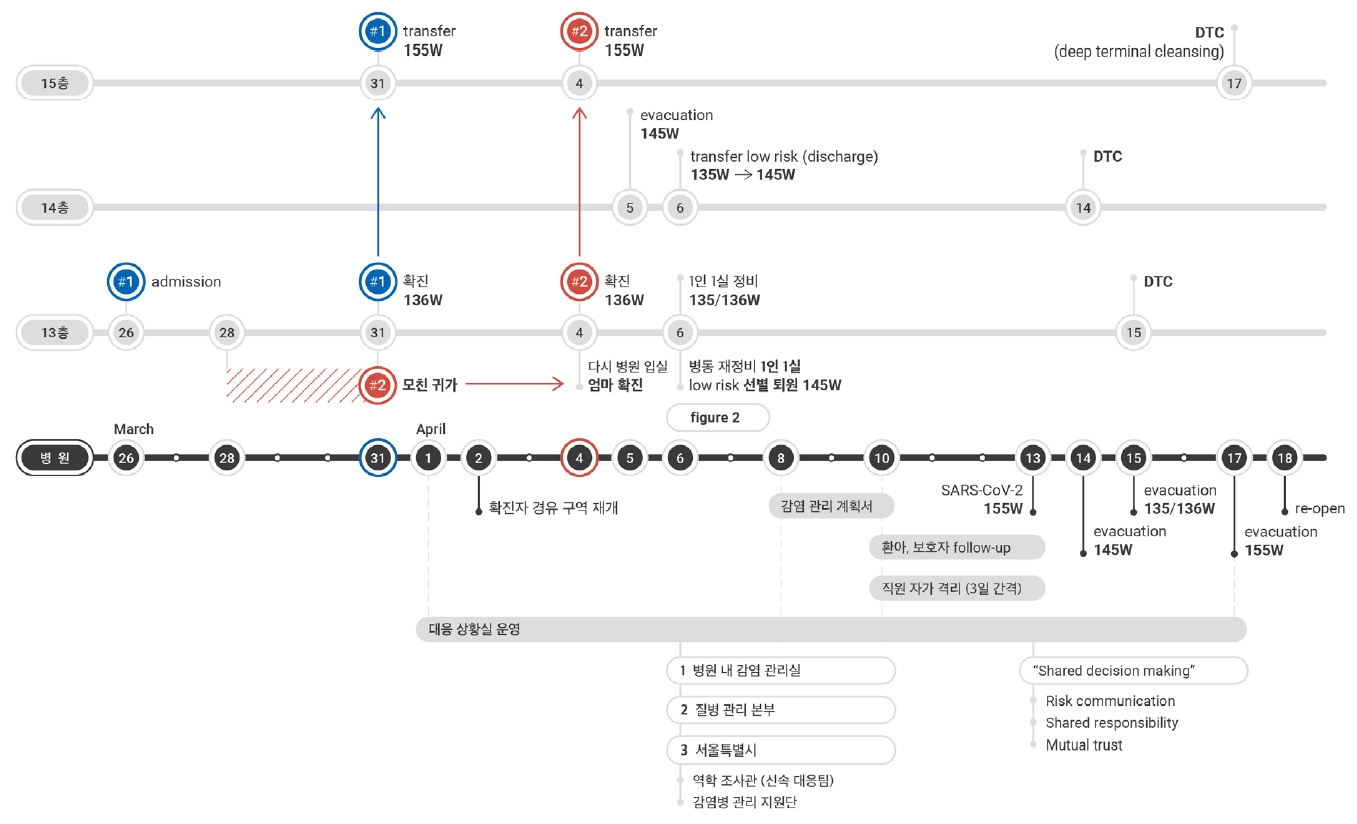

Second, wards on the same floor where the COVID-19 positive patient stayed were quarantined. However, it was difficult to provide individual isolation. Therefore, contacts in the same room or ward as the COVID-19 positive patient were quarantined to single-occupancy rooms, assigned preferentially based on risk. The rest of the patients were quarantined in double- or triple-occupancy rooms with a safe distance between them. The COVID-19 task force allowed for existing patients of the No.145 ward to other ward to disperse for two days, and low-risk patients from the No.135 ward were moved to the No.145 ward and then to single-occupancy rooms (Figure 2).

Third, psychological distress started to develop over time. Quarantined individuals suffered from increased irritability and anger, reacting with increased feelings of stress. They even complained and threatened to sue doctors and nurses. In an extreme case, the mother of one contact had suicidal ideation. The COVID-19 task force determined that emotional disturbances such as terror, frustration, depression, anxiety, and boredom were caused by insufficient supplies and inadequate resources. To take assist with patients’ mental health, doctors made rounds more often to reassure patients and provide them with more information. Moreover, a customer support team was organized to assist with psychosocial management. This team monitored the psychosocial needs of the patients in quarantine and provided relevant support. The patients in quarantine were permitted to take short, individual walks through the corridor. They were also offered their favourite foods at mealtime, such as iced coffee. Patients from the No.135 ward, those with low-risk contacts, were released, and the ward was shut down. These children were medically discharged and were each connected with a community health centre to assist in maintaining isolation at home, with the hospital providing transportation, such as ambulances, from the hospital to their homes. Through these efforts, other patients under quarantine became hopeful, with a reasonable expectation for discharge and recovery.

This case is an example of the multidirectional effort and the multidisciplinary team approach is important when a nosocomial outbreak happened in the hospital. They controlled the nosocomial infection through early detection of COVID-19, immediate response, extensive contact tracing with testing, and unstinted effort.

In conclusion, the collaboration of the hospital’s infection control team, local community officials, and national decision-makers to communicate and share responsibilities for nearly 20 days resolved the situation at the hospital with no further spread of infection (Figure 3). Since children are more vulnerable than adults insofar as they are extremely dependent on their parents or guardians, for confirmed COVID-19 cases in paediatric wards, it is important to consider the status of both the patients and their guardians, and to provide not only medical treatment but also emotional support.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are deeply grateful to the staffs at Asan Medical Center, Songpa-gu Community Health Center, Seoul Metropolitan Government COVID-19 Rapid Response Team (SCoRR team) and to local health officials. Above all, we would like to express our sincere gratitude to patients and families for their understanding, support, and cooperation at Asan Medical Center.

References

1. Zhan J, Li H, Yu H, Liu X, Zeng X, Peng D, et al. 2019 novel coronavirus(COVID-19) pneumonia: CT manifestations and pattern of evolution in 110 patientsin Jiangxi, China. Eur Radiol. 2021;31(2):1059–68.

2. Park M, Cook AR, Lim JT, Sun Y, Dickens BL. A Systematic Review of COVID-19 Epidemiology Based on Current Evidence. J Clin Med. 2020;9(4.

3. van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, Holbrook MG, Gamble A, Williamson BN, et al. Aerosol and Surface Stability of SARS-CoV-2 as Compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(16):1564–7.

- Related articles in PHA